Economist Loren Brandt on China's Industrial Policy

Aside from biweekly SCCEI China Briefs, we periodically feature relevant content from other SCCEI programs, like this presentation on China’s industrial policy by economist Loren Brandt.

Loren Brandt is the Noranda Chair Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, specializing in the Chinese economy. He is also a research fellow at the IZA in Bonn, Germany. Brandt has published extensively on China’s economy and has conducted household and enterprise survey work in China and Vietnam. His current research focuses on entrepreneurship, industrial policy, and economic growth.

His remarks have been edited for length and clarity.

Loren Brandt: I'm going to start with a little quiz.

Can anyone guess what these four industries have in common? Lithium batteries, EVs, solar panels, and shipbuilding.

If we examine these four industries and look at the percentage of global output that China produces, we see that China is the number one producer in all of them. In two of them it produces more than 50% of the global output, and in two of them it produces about 75%. Clearly, China dominates these four industries.

This leads us to an important question, one that I ask as an economist interested in China and its relationship with the United States: How do we explain this success? How do we define success in this context? And how do we explain China's dominance in these four industries? What is the key to this success?

What have been the benefits of this enormous growth and the level of success that we observe?

But have there been costs? I believe this is a question that interests all of us in various ways. At the center of this discussion is industrial policy.

Today, we aim to understand the role of industrial policy in this remarkable industrial success in China.

We need to be precise in defining what we mean by industrial policy.

For economists, when we talk about industrial policy, we are referring to government efforts targeting specific sectors, technologies, and firms. It is a precise and distinct concept. Governments employ various policies to influence overall economic activity and stabilize the business cycle through monetary and fiscal policies, but that is not what we are discussing here. Industrial policy focuses specifically on targeted industries.

Industrial policy has a long history.

In development economics, there has been a long-standing debate about the role of industrial policy in Japan's post-World War II success, as well as its influence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Similar discussions arise when examining Korea and Taiwan, making this an ongoing and complex debate.

Even in the United States, industrial policy has played a role. Consider Alexander Hamilton’s proposals over 200 years ago: he advocated for tariffs to protect America’s nascent industries from British competition.

Despite its history, there is considerable debate over the effectiveness of industrial policy. Nobel laureate Gary Becker, from the University of Chicago, held the view that the best industrial policy is no industrial policy at all—a perspective aligned with the Chicago School of thought. Meanwhile, Dani Rodrik, a highly influential economist over the past two decades, argues that the key question is not whether industrial policy should be implemented but how it should be executed.

An increasing number of economists now argue that industrial policy has merit. The question is not whether to have it but how to implement it effectively.

From an academic standpoint, these are difficult questions. Empirically, assessing the effects of industrial policy is challenging.

Why might industrial policy have value? What is its economic rationale?

To simplify, proponents of industrial policy argue that markets do not always function efficiently. Left to their own devices, markets may not produce desirable outcomes. One classic argument, particularly in development literature, is infant industry protection. Developing countries seeking industrialization often struggle because their emerging firms cannot compete with established firms from mature economies. The argument for industrial policy is that temporary protections, such as tariffs or subsidies, allow these industries time to develop and eventually compete on their own.

Similarly, industrial policy is often justified in cases of research and development (R&D). Certain types of R&D have broad benefits but generate spillovers that individual firms may not fully capture, leading to underinvestment. Government intervention, such as subsidies, can encourage essential R&D efforts.

Another justification arises in industries with complex supply chains that require significant coordination among upstream and downstream firms. In such cases, the government may play a role in facilitating investment and coordination.

However, just as markets can fail, so can politics. Political failure may not resolve market failures and can sometimes lead to even worse outcomes.

What are the key instruments of industrial policy?

Governments have numerous tools at their disposal, including subsidies, preferential access to finance, tax breaks, and tariffs. Some of these instruments comply with World Trade Organization (WTO) regulations, while others do not.

How does industrial policy fit into the Chinese context?

China reached a turning point in the mid-2000s when it felt it had exhausted the benefits of its labor-intensive manufacturing and incremental innovation model. The Chinese government recognized that a shift was needed. A quote from the Ministry of Science and Technology in 2005—long before the "Made in China 2025" initiative—illustrates this shift: "We are aiming at the forefront of world technology development."

At the time, China’s per capita GDP was only about 15% of that of the United States. Despite being early in its development, China decided to transition from a follower to a leader in high-tech industries. This shift was reflected in several policy documents, including the Medium- and Long-Term Plan for Science and Technology (2006), strategic plans for emerging industries (2010), and Made in China 2025 (2015). These policies aimed to move China toward indigenous innovation and technological development rather than relying on foreign technology. So Made in China 2025 had really deep roots.

China's industrial policy is hierarchical and top-down, with central, provincial, and municipal governments aligning their strategies with national plans. Officials at all levels have career incentives to promote these policies, reinforcing their implementation.

The objectives of China’s industrial policy included achieving sustainable, balanced, and green growth. Environmental concerns, a significant issue at the time, were integrated into these strategies. Another major goal was reducing dependence on advanced economies by fostering homegrown technological capabilities.

The rapid increase in R&D expenditures in China reflects these policy objectives. By 2018, China’s share of global R&D investment was on par with that of the United States. Similarly, patent applications from China surged, demonstrating the country’s focus on technological advancement.

Despite massive investments in R&D, infrastructure, and education, China’s economic growth has slowed in recent years. In per capita terms, China’s GDP remains around 20–25% of the U.S. level. And I’d argue that probably for the last few years, China’s GDP has been growing by one or two percent. This raises a fundamental question: Why is growth slowing despite China’s massive investments?

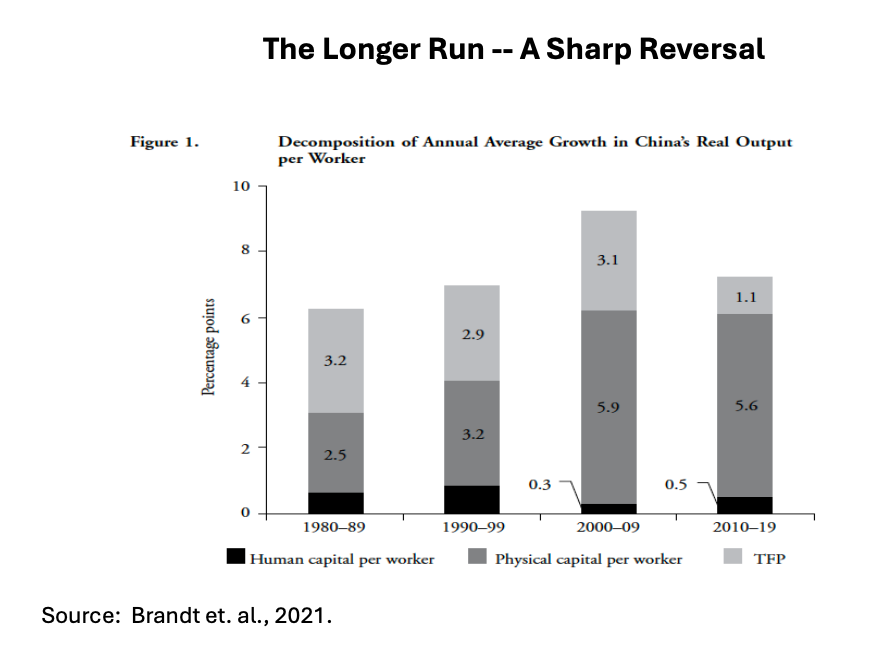

One explanation lies in declining productivity growth. In the first three decades of reform, China’s productivity growth was around 3% per year, sustaining high investment returns. However, since the mid-2000s, productivity growth has stalled, and returns on capital investment have plummeted.

Industrial policy may be a contributing factor. In some industries, such as solar panels, excess capacity far exceeds global demand, distorting market signals and leading to inefficiencies. The same pattern is visible in shipbuilding, where heavy subsidies helped China increase its global market share from 10% in 2005 to 50% in 2015. However, these subsidies have created distortions, and the benefits have not necessarily accrued to China itself.

The global response to China's industrial policies has been mixed. While consumers benefit from lower prices for solar panels, batteries, and shipping, the resulting overcapacity has disrupted industries in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere. Some of China’s own firms are also suffering due to the inefficiencies created by these policies.

The broader question is whether China’s industrial policies have ultimately helped or hurt the country. The economy remains unbalanced, and many of these policies have resulted in tensions with trading partners.

China’s growing trade surplus—now about 2% of global GDP—is raising concerns, much like the surpluses previously seen in Germany and Japan, but this time China is really off the charts (see chart above). The current global policy environment is attempting to address these imbalances.

In conclusion, while China’s industrial policies have driven technological progress and global competitiveness, they have also led to significant challenges at home and abroad. These policies continue to shape China’s economic trajectory and its interactions with the world.